The following is a guest article by Scott Williams, Director of Provider Directory Research & Development at Epic, and David Hoffert, Director of Provider Directory Public Policy at Epic

Every day in America, sick patients are sent to medical providers who no longer practice where the patients were told to go. Private medical records are sometimes faxed to places as inappropriate as auto repair shops. Insurers, working to prevent fraud, inadvertently deny legitimate claims and care authorizations simply because they haven’t been notified of a provider’s new location. These breakdowns delay necessary care, increase stress on families, drive up waste, and open the government up to fraud.

Every day in America, sick patients are sent to medical providers who no longer practice where the patients were told to go. Private medical records are sometimes faxed to places as inappropriate as auto repair shops. Insurers, working to prevent fraud, inadvertently deny legitimate claims and care authorizations simply because they haven’t been notified of a provider’s new location. These breakdowns delay necessary care, increase stress on families, drive up waste, and open the government up to fraud.

All these things happen because the United States lacks a single, reliable source of truth for the most basic information about physicians, such as their practice location, contact information, and specialty. Without this source of truth, patients and insurers are left playing a real-life game of “Where’s Waldo” as they try to locate physicians. And some hospitals are even paying staff to read obituaries so that they don’t send discharged patients to deceased specialists.

On June 3, Dr. Mehmet Oz, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Administrator, at a meeting with health technology stakeholders in Washington, DC, announced that CMS plans to help fix these problems by building a national healthcare directory, starting with provider information. He has laudably identified the lack of a well-functioning national provider directory as one of the problems that creates waste, inefficiency, and opportunities for fraud throughout the healthcare ecosystem.

As the nationwide leader in healthcare interoperability, Epic is working to address the technical complexities of building provider directories. This is a problem that neither the government, providers, payers, nor technology developers can solve on their own. Epic’s R&D team put together a provider directory concept paper for the consideration of CMS and the broader stakeholder community.

The following is the full concept paper Epic sent to CMS. We would welcome feedback; please send your thoughts to Scott Williams (scwillia@epic.com) and David Hoffert (dhoffert@epic.com).

1. Introduction

This paper reviews current problems and their causes for provider directories and the lessons learned from previous efforts to unify such directories. Further, it identifies key components for consideration when building a National Provider Directory and a detailed action plan to follow.

2. Current State

A. Health Ecosystem Problems

The U.S. healthcare system lacks a single, trusted directory for even the most basic provider and organization information, such as who practices where, what services they offer, where they’re “in network,” and where to find Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resource (FHIR) endpoints. Existing databases have been stretched far beyond their original purposes, yet none offer the real-time, API-based reliability—or even basic data correctness—that the digital health ecosystem demands.

Without a national, authoritative, API-integrated directory, billions of dollars are wasted on administrative burdens, health IT innovations stall, and healthcare quality is harmed. Patient care is delayed when referrals are faxed to inappropriate places, such as auto repair shops, or sent to providers who have retired or moved practice locations. Even when sent to the correct location, faxing referrals is slower and more error-prone than electronic transmissions would be. Care can also be delayed when insurers, working in good faith to prevent fraud, deny or delay legitimate prior authorizations because they haven’t been notified of a provider’s new location.

Recent analyses have estimated that provider organizations spend nearly $2.8 billion per year on directory maintenance while payer organizations spend an additional $2.1 billion to $2.3 billion. Because many current databases must be updated manually, the process is time-consuming and therefore costly. Those costs are multiplied each time another database is enlisted to collect directory information. Establishing a proper National Provider Directory (NPD) would likely not only reduce abrasion in the system and improve quality outcomes but also save money.

B. Underlying Causes

These problems arise for a very simple reason: much of the data in today’s provider directories is incorrect, for many different reasons. Some of the data was correct when it was first submitted, but then became out of date when it was not updated as things changed. Other data was always incorrect because the person responsible for submitting it didn’t know the correct answer and didn’t have an easy way to determine it, so it was faster and easier for them to make their best guess. Still, other data is correct but incomplete, rendering it useless.

The fact that there are multiple competing directories is also a problem in and of itself. Without a centralized provider directory, payers, provider organizations, and HIEs must maintain their own siloed copies of national or regional external provider directory information, often gathered by “portalitis” workflows or emails across organizations. Federal databases contain basic data but lack the richness needed for interoperability. Private-sector solutions are typically limited in scope, accessible only to their customers, and often provide only basic reference data without the depth needed for interoperability. Some prioritize interoperability but lack core reference details.

While there is no one cause of data incorrectness, each cause can be identified, and steps can be taken to prevent that cause in the new NPD. To successfully address the problems faced by current directories, NPD will need to get three things right: it will need to have the right data structure populated by the right contributors using the right processes. This paper explains and makes recommendations for each of these areas and then provides a detailed plan for building NPD from the ground up, with appropriate phases and intermediate milestones to ensure ongoing benefit.

3. Lessons Learned for Provider Directories

A. Right Data Structures

How the data in NPD is organized and stored will affect, independent of any other design choice, data completeness and correctness. Consider, for example, three options for storing provider address information in a directory:

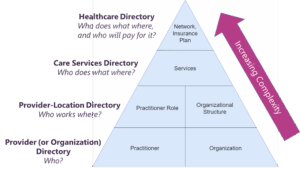

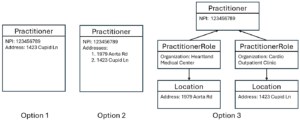

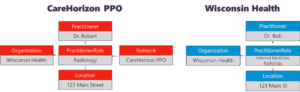

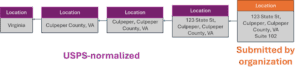

Figure 1: Three possible architectures for storing provider address information

Prior to the late 2010s, Option 1 was used by the National Plan and Provider Enumeration System (NPPES), whose primary purpose is to manage National Provider Identifiers (NPI) under HIPAA, but which has expanded over the years to serve as one of the nation’s de facto provider directories. Option 1 works well so long as providers only ever work for one employer at a time; if a provider changes employers, the new address information can overwrite the old.

However, many providers work simultaneously for multiple employers, at different locations, and Option 1 is incapable of reflecting this reality. Around 2018, NPPES recognized this and moved to Option 2. While multiple addresses can now be stored, the information is not useful without being associated with specific organizations. If a provider wishes to make a referral to NPI 123456789 at Heartland Medical Center, they do not know which of the listed addresses should be used. By dividing concepts into multiple distinct FHIR resource types, only Option 3 properly captures the correct and complete information needed for referral and prior authorization workflows.

These and many other data modeling challenges have been considered and addressed by various FHIR working groups, and there is near-universal agreement that NPD should use FHIR resources to build the directory and FHIR APIs to communicate bidirectionally with other databases. FHIR uses resources to represent entities in the real world, such as providers, clinics, or insurance plans. These resources are independent, allowing each participant in the healthcare ecosystem to own and maintain the specific parts of the directory for which they are responsible.

FHIR implementation guides define which resources and APIs are needed to build and interact with a FHIR database. The most comprehensive implementation guide for U.S. provider directories uses nine key FHIR resources:

- Practitioner: Individual provider identity

- PractitionerRole: Contextual data – roles, locations, specialties

- Organization: Organizations and organizational hierarchy

- Location: Physical addresses and sites

- HealthcareService: Offered services and specialties

- Network: Health plan provider networks

- InsurancePlan: Health plan

- OrganizationAffiliation: Relationships between organizations (including interoperability networks in which they participate)

- Endpoint: Technical contacts for interoperability and APIs

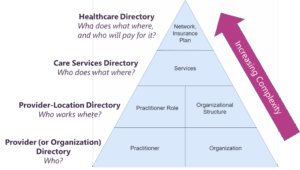

However, this structure need not be built all at once. A subset of these resources can be used to build a simpler directory that answers a limited set of questions. Subsequently, complexity can be introduced with the addition of more resources. For example, we recommend building a comprehensive provider directory in four sequential phases:

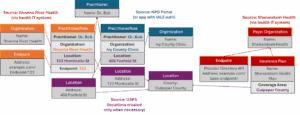

Figure 2: Hierarchy of FHIR directories and their data elements

To save time and ensure alignment with the larger healthcare ecosystem, NPD should be built by implementing, or taking inspiration from, existing FHIR directory implementation guides. The HL7 FAST National Directory of Healthcare Providers & Services (FAST NDH) implementation guide is a good starting point because it uniquely meets the following criteria:

- Designed for the U.S.

- Supports providers, provider organizations, interoperability networks, and payer organizations

- Supports FHIR-based submission of directory data from primary sources

- Builds on top of the Da Vinci PDex Plan Net FHIR directory implementation guide (a payer-focused FHIR directory implementation guide that is endorsed by CMS as the recommended standard for its Provider Directory API requirement).

While the overall FAST NDH appears complex when presented in a single diagram, this is because it incorporates each phase of provider directory described above. However, it can be implemented iteratively, starting with a Provider-Location Directory first to achieve early successes with limited scope, and building to networks and payer integration in a later release.

Figure 3: FAST NDH resource diagram (simplified), divided into iterative parts

B. Right Contributors

In current directories, individual providers are expected to submit information about themselves, their organizations, and their IT systems manually via web portals. As a result, they are asked to submit data they often do not know and are not actively managing, because separate electronic systems, such as EHRs, are already managing it for them.

To support a modern healthcare technology ecosystem, workflows like electronic referrals, prior authorizations, and claims processing require not just provider details, but also foundational information about the health IT systems involved. For example, sending an electronic referral requires knowing how to reach the target system—something only possible through a directory that includes API endpoints, which cannot be maintained via provider self-entry in a portal.

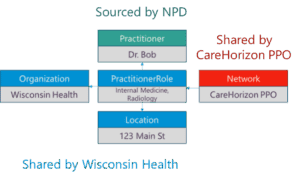

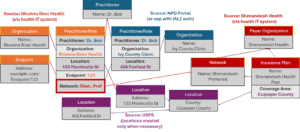

Today, federal databases, health IT systems, HIEs, state licensure boards, and health plans often have copies of the same or similar data. NPD will need policy decisions about what its sources are and who is considered a primary source of what information. If two sources can submit the same data, the directory can end up with duplicate information, which would require a user to reconcile, as the following diagram indicates:

Figure 4: A payer and provider organization could have largely duplicative but inconsistent information about a provider

Historically, directories like NPPES or health plan portals have solved this problem by assigning the provider (or an organizational delegate) to be the source of truth for all their data. However, different entities in the healthcare ecosystem are natural sources of truth for different data elements, and FHIR’s modular data structure allows for different sources to own different parts of the provider directory. For example, a health plan could submit whether a provider is in-network at a specific location, but should not submit the provider’s scheduled hours.

The best contributor for a particular type of data will be the entity that is

- Reasonable, unique primary source of the data

- Already maintains the data and uses it in operations

- Motivated to have accurate data for the element(s) it submits.

Having the entity that already knows and maintains each piece of information be responsible for submitting it to the directory will make it easier to submit, which will, in turn, make it more likely to be submitted frequently and more likely to be correct. When inaccuracies are identified, they are easier to correct because the single source of truth is easier to identify and contact quickly. We recommend the following assignments for primary data sources in NPD.

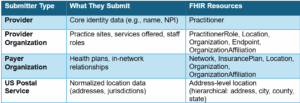

Individual Providers

NPPES (or NPD itself if it fully replaces NPPES) should remain the source of truth for provider NPIs and core identity data about individual providers (e.g., name and demographic info). It should be scoped down to focus solely on such core identity information and continue to be updated by individual providers. This data will be used to populate the Practitioner resources in the directory.

To reduce provider “portalitis,” NPD should reduce the number of federal provider data portals instead of adding more. NPD must be built as an extension of NPPES, or fully replace it; ideally, it would also unify workflows like the Provider Enrollment, Chain, and Ownership System (PECOS)— intended for provider Medicare enrollment tracking—and DEA registration within a single portal.

Healthcare Organizations

Healthcare organizations should populate the PractitionerRole, Organization, Location, HealthcareService, Endpoint, and OrganizationAffiliation resources. These organizations already manage all this data as part of their health IT systems, and their correctness is required for daily operations. This gives them the greatest incentive to maintain accurate data on these data elements and puts them in the best position to submit that data to NPD.

Payer Organizations

Payers should also submit information for Organization resources—but only for those Organization resources representing payer organizations. Payers should also be responsible for populating InsurancePlan and Network resources and tying them to provider organization PractitionerRole resources. This would be better than CMS’s current requirement for insurance plans to offer standalone Provider Directory APIs, since it would provide a single place to look for all provider directory content and eliminate the need to maintain duplicative infrastructure.

Credentialing and Licensure

Other relevant information should always come from the most natural source of truth for that data. For example, the Practitioner resource in FAST NDH includes information—such as licensure, certifications, and sanctions—that should not be populated (or maintained) by NPPES. Instead:

- Certification information should be populated by the appropriate certifying boards

- Licensure and sanction information should come from state licensing boards and the National Practitioner Data Bank

The diagram below provides an example of how each healthcare entity can submit and maintain data relevant to their operations, maintaining a single source of truth for each piece of data.

Figure 5: Example of federated data ownership per FHIR resource; separation of concerns means different sources can attest to data without requiring reconciliation

C. Right Processes

Real-Time, Machine-Readable Data

There are two primary methods that could be used to populate NPD:

- Manual attestation via a web portal, optionally prepopulated by IT systems

- Automated submission via APIs (e.g., through existing interoperability networks)

Portal attestation is a time-consuming and error-prone process. Because it depends on manual intervention, updates often lag behind real-world changes, leading to outdated information unless providers are compelled to attest frequently. But increasing update frequency exacerbates the risk of human error (e.g., transposed digits or incorrect locations), creating a tradeoff between data freshness and reliability.

Health IT systems store almost all the information that is being submitted through these portals already. If these systems could connect to a national directory and submit data via APIs, the data could be submitted automatically, in real-time, with greater data richness, in a FHIR format that can be used to “axe the fax.”

While a manual option should remain available—especially for organizations without advanced health IT infrastructure—API-based submission should be the default. Machines don’t tire or make clerical mistakes, which significantly improves data quality.

Machine-based interoperability also enables key healthcare workflows (e.g., referrals or claims processing) by relying on rich, system-readable directories (e.g., FHIR-based). These workflows often depend on complex combinations of network, system, and endpoint data that are not feasible to maintain via manual entry on a national scale.

Integrating with Exchange Frameworks

A provider directory by itself is a reference tool: good for looking up information, but not for enabling electronic workflows like prior authorizations or referrals. To execute these complex workflows, users need confidence in things such as endpoints accurately representing providers, being current and secure, and being reachable.

For individual app developers to gain this confidence, they need to form relationships with every entity with which they wish to exchange. Rather than doing this one by one, joining a network can allow all parties to benefit from shared connectivity, common standards, and mutual trust agreements. Each app developer can build a single connection to a network instead of individual connections to every entity in that network, saving time and resources.

Networks provide:

- A trust and governance framework to ensure appropriate use of PHI

- Scalable connectivity between systems, including endpoints and how they are associated with real-world entities from the provider directory

- Standards to define how data is formatted and transported

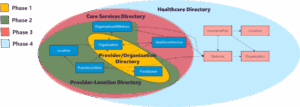

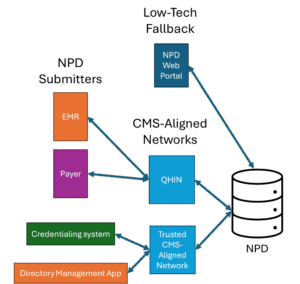

NPD alone cannot achieve goals like “axe the fax” and “kill the clipboard.” Real, scalable data exchange will happen within CMS Aligned Networks. These networks are where the directory becomes actionable, enabling the workflows that rely on trusted, secure, and interoperable data.

At the same time, NPD faces its own integration challenges. Like any app developer, NPD must determine how to gather data through APIs without needing to establish individual connections with every potential data source. Attempting to manage one-off integrations at scale would be resource-intensive and unsustainable. Additionally, this approach would reduce the benefit of participating in NPD for initial adopters, since there would be little useful data available at first. This would slow the uptake of NPD, creating a vicious cycle that could mean it never got off the ground.

A practical solution to both challenges is to designate a trusted subset of CMS Aligned Networks—those with a proven track record of maintaining high-quality directories—as authorized submitters to and readers from NPD. This allows NPD to receive robust, reliable data at scale while reinforcing the broader ecosystem of interoperable exchange and allowing CMS to delegate governance and connectivity. Due to the robustness and data quality of the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA) network, it would make sense for it or its Qualified Health Information Networks (QHINs) to serve as early adopter contributors to prove the concept.

Figure 6: Recommended approach for exchange framework integration

By integrating the provider directory into networks with strong governance, those networks can improve the quality of data in the directory in several ways. A core requirement is the ability to uniquely identify each legal entity submitting data and to restrict attestation rights accordingly. For example, if UW Health is listed in the directory, there must be a way to ensure that only UW Health can attest to or manage its data and delegate access appropriately. Without such safeguards, NPD risks becoming inconsistent, duplicative, and untrustworthy. Any providers in multiple contributing networks would need to select which network submits their directory data.

Governance is also essential for addressing NPD’s biggest challenge: data quality. Submitters must be accountable for the accuracy of their contributions. Organizations that submit incorrect data should face penalties and be required to make timely corrections. Conversely, those providing high-quality data should be recognized and rewarded. Some disputes, such as disagreements over shared clinic ownership, may require human resolution to prevent duplicate entries.

4. Building the NPD

In this section, we offer a recommendation for how NPD could be created in alignment with the previous section’s learned lessons. This is intended to be a starting point for ideas and discussion, not a final design.

Core Concept

NPD is a single database and website that shows who delivers care, where they deliver it, what they do, who’s in-network where, and how other systems can connect to them electronically. NPD is a federated FHIR directory, exchanging data with multiple CMS Aligned Networks to build a comprehensive, nationwide picture of the healthcare landscape. It draws data directly from primary sources (providers themselves, provider organizations, payers, apps), each contributing only the information they are best positioned to own.

It is designed to be:

- Machine-readable as a FHIR server and a partial or forked implementation of the HL7 FAST NDH implementation guide

- Human-accessible via a public-facing website and data management portal

- Governed and secure, with clear ownership, access control, and audit trails

- Iterative and extensible, starting simple and expanding over time

- A singular public repository of FHIR endpoints with sufficient data richness to tie to a FHIR map of real-world healthcare entities

How It Works

NPD offers two submission paths:

- Submission Via Trusted Network: Any organization can use a CMS Aligned Network to submit their directory data to NPD, and keep it in sync with their operational database

- Web Portal: For organizations without API capabilities, a free CMS-hosted portal supports guided data entry and review, and delegated access for staff (using CMS’s Identity and Access Management [I&A] system)

NPD should have several ways to view the data:

- A public website for patients and providers to search and reference

- Open, read-only FHIR APIs

- Regularly posted flat files with deltas and full directories

Who Participates

Each entity submits and manages only the data that they are primary sources for, and corrections to incorrect data must be made in the primary source.

Provider Experience

A provider (or a delegate) signs into NPD using their I&A login. NPD allows them to view and edit all information associated with their Practitioner resource. The onboarding process walks them through a form populating and reviewing the data. They can edit their Practitioner resource, mark it as verified, and flag any incorrect information other sources have submitted about them.

Low-Tech Provider Organization Experience

An organizational delegate signs into NPD using their I&A login. NPD allows the user to view and edit all information associated with the organization’s data: Organizations, PractitionerRoles, Endpoints, OrganizationAffiliations, and Locations. The onboarding process walks the user through a form populating these fields, with an option to prepopulate the forms with a flat file or bulk FHIR file upload.

High-Tech Provider Organization Experience

An organization onboards to and connects through a CMS Aligned Network. As part of that network, the organization shares its directory data with the network. This information flows automatically into NPD without intervention. Networks must implement a way to process, route, and/or display poor-quality data flags. An organization can make a change to a provider’s status in an EHR or a network-connected app, and the change is propagated to the network and through to NPD.

Health Plan Experience

Payer organizations onboard to a CMS Aligned Network to provide live in-network status. Payers are responsible for sharing their plans and associating PractitionerRoles with in-network status in their plans. Payers own their Organization, Network, InsurancePlan, and Location resources.

Handling Locations

In FHIR directories, location represents physical location, like an address, not organizational facilities. Location resources should be hierarchical: suites should be under an address Location resource, the address should be under a city or county resource, and the county should be under a state resource. This can help determine coverage regions for payer networks.

Ideally, location data would be deduplicated, so it is easy for an API to look up all the organizations that share a facility, or all the organizations in a jurisdiction (e.g., city, county, state). It would also be advantageous to be able to match location data reported by two organizations.

This can be solved by having Location resources be managed via the US Postal Service’s address APIs. When NPD users submit a Location, it should be required to correspond to a USPS address or point to a parent Location resource that is a USPS address. For example, if an organization shares a provider clinic with a location, “123 State St, Culpeper, Culpeper County, VA, Suite 102”, this could be represented as:

Figure 7: Federated FHIR Location resource hierarchy

Handling Services

CMS creates a simple, standard list of “patient-facing” services, such as specialties and common conditions for which patients would seek treatment. These resources are submitted to NPD with CMS as the defined submitter, so no one else can create or edit them.

Organizations can optionally use these HealthcareService resources as “tags” they can put on providers and organizations to let patients know what services they can expect.

This approach significantly simplifies services interoperability while getting most of the value for patient-facing provider search services.

Keeping the Data Right

To ensure data quality and trust, NPD includes:

- Ownership Control: Each organization submits only data for which it is a primary source and has access to edit only the data it submits

- Flagging and Resolution: Users can flag incorrect entries; flags are routed back to the data owner for verification, and the verification status is visible to users

- This could be modeled as a Task resource

- Attestation and Verification: In general, NPD’s data model policy for sources limits cases where multiple sources attest to the same data; in cases where this is unavoidable, implementing an attestation and verification workflow may be required

- Transparency: Every record shows who submitted it, when it was last updated, and whether and when it has been verified

- Feedback-Based Incentives: Submitters are scored on data freshness and flag resolution, building an ecosystem of accountability and trust

Avoiding Contributing to Provider “Portalitis”

To avoid contributing to the fragmentation caused by redundant portals, NPD must avoid duplicating workflows already handled by NPPES and I&A. There are two strategic paths forward:

- Build new NPD workflows as an extension of NPPES; limit NPD’s scope to leverage NPPES for enumeration and identity management

- Fully replace NPPES with NPD, using I&A/IDM for identity and access control

We do not have sufficient insight into the technical infrastructure of NPPES to make a definitive recommendation. The decision should weigh the cost and complexity of maintaining and modernizing NPPES versus migrating a provider and organization enumeration process to NPD.

“Portalitis” in Credentialing and Payer Portals

Today, provider enrollment in health plans is largely portal-based, with each payer collecting a similar but unstandardized set of data. As a result, portals are likely to persist, as it is unrealistic that a single portal or transaction type could collect all the data that is needed.

NPD can add the most value by establishing itself as a high-quality, API-based baseline for provider and location information and interoperable endpoints related to that information. Portals can use reliable APIs to pull the information they need automatically, and credentialing and payer systems can be on the same page with provider systems about provider and location relationships.

5. Action Plan

A. Early Adoption (by EOY 2025)

This roadmap outlines the steps CMS could take to build a functioning NPD by the end of this year. The objective of this phase is to move quickly to create a functioning directory. This prototype will also serve as a testing ground for scalable infrastructure, FHIR specification, and policy development. While governance, data quality enforcement, and access control are essential to realizing the long-term vision for NPD, they will take longer to develop than this technical core and are not needed if there is a small number of early adopters. CMS could provision access to any of the CMS Aligned Networks or organizations for an initial demonstration of the database.

Goal for CMS: Launch a live, FHIR-based NPD prototype that allows early adopters to submit basic provider-location directory data and corresponding API endpoints.

1. Define Core Directory Scope

Establish the Base Directory Structure: Define a preliminary specification for NPD’s FHIR APIs and resources, prioritizing developer documentation over a formal implementation guide during the prototyping phase.

- Recommended FHIR Resources: Utilize profiles from US Core for Practitioner, Organization, Location, Endpoint, PractitionerRole, Network, and InsurancePlan resources

- Draw from established FHIR directory implementation guides like Da Vinci PDex Plan Net and HL7 FAST NDH for foundational concepts

2. FHIR Server Implementation

Select a FHIR Server: Implement the backend using a mature, off-the-shelf FHIR server to accelerate development and ensure standards conformance. Building a server from scratch is not recommended.

- Commercial Recommendations: Firely Server (.NET), Smile CDR (Java), and Aidbox (Java) offer robust FHIR conformance and flexible deployment options

- Open-Source Alternatives:

- HAPI FHIR: A mature, Java-based FHIR implementation that forms the core of Smile CDR and is used in multiple CMS projects

- Microsoft FHIR-Server: An enterprise-grade, .NET-based server optimized for Azure and built on top of the Firely SDK

3. Data Ingestion and Management

Bulk Import: Create a bulk import API (as defined in the HRSA UDS+ FHIR IG).

- This will be used by:

- The NPPES-to-NPD feed to bulk submit Practitioner resources

- Submitters to bulk submit bundles of their respective directory resources

- Some FHIR servers may implement this, but it is not yet specified in a published version of the HL7 Bulk FHIR IG; specify bulk import behavior in developer documentation for now

Automated NPPES-to-NPD Data Flow: Establish an automated data pipeline to ingest the weekly NPPES flat files or establish direct feed from NPPES to NPD for more timely data. This process will map core NPPES identity fields to the Practitioner resource and bulk-import the data into NPD.

- Context-specific data like addresses or specialties from the NPPES record should be omitted from the core Practitioner resource

Data Submission & Retrieval: Utilize the standard FHIR create and update interactions for data submission and read and search interactions for retrieval, all of which are natively supported by mature FHIR servers.

[Optional] Periodic Publication: Instead of having numerous consumers trigger individual $export operations, CMS should publish bulk FHIR flat files on a recurring schedule. This improves efficiency, reduces redundant system load, and streamlines large-scale consumption.

- Implement this by regularly triggering $export operations, publishing bulk files to an accessible location, and providing a manifest file with metadata to guide clients on which exports to retrieve; consider restricting the $export operation to just this regular trigger to limit overall system load on NPD

- The Argonaut Project FHIR Accelerator is actively designing updates to the HL7 FHIR Bulk Data IG to formalize and standardize this idea

4. Access Control

Authentication and Authorization: Implement the SMART on FHIR (Backend Services) framework for server-side authentication and authorization, which is supported by most mature FHIR servers.

Resource-Level Ownership: Implement a mechanism to enforce data ownership, ensuring submitters can only modify resources they have created. This can be achieved using a custom extension on each resource, enforced by a server-side interceptor.

- In Sequoia’s organization-based directories, this is represented in an extension which points to the logical entity responsible for the resource

- This could also be implemented with Provenance resources

Define Authorization Scopes:

- Public: Read-only access to all resources

- NPPES: Write access for Practitioner resources

- Provider Organization Submitter: Write access for Organization, Location, Endpoint, and PractitionerRole resources

- Payer Organization Submitter: Write access for Organization, Network, InsurancePlan, and Endpoint resources

5. (Optional) Onboarding

Web Page: Create a public website for NPD, with onboarding steps and developer documentation.

Onboarding Process: Establish a formal application process for data contributors to be verified and provisioned with API credentials, modeling the process on existing CMS systems like DPC, BCDA, and Blue Button 2.0. Create a simple developer-focused web page with documentation.

6. (Optional) Auditing

AuditEvent resources should be created for auditing actions performed on the FHIR server.

Figure 8: The federated NPD directory after the Early Adopters phase; provider and payer directories are not integrated, but the Provider Directory API can be used to search the payer networks

After this phase, we have achieved an open, interoperable FHIR provider directory that allows for automated submissions from payers and providers and proves the technical concepts. We have not yet solved creating a single, fully deduplicated, reliable source of truth—we will need governance and an access control policy built on organizational identity proofing to move forward to that.

B. NPD Phase 1 (Targeting EOY 2026)

This phase transitions NPD from a prototype to an API-based, federated directory. The focus is on establishing robust data submission channels, improving data completeness, and introducing foundational services while consolidating provider workflows to reduce administrative burden. The goal is to create a national interoperability infrastructure in the form of a FHIR provider directory. This technical foundation can be extended in later phases to a single national source of truth.

- Goals for CMS

- Launch a fully functional NPD portal that allows providers and organizations to directly manage their directory data

- Establish organizational identity standards

- Enable scalable data submission through CMS Aligned Networks

- Web Portal Front-End

Create a user-friendly interface for providers and small organizations to directly manage their NPD data. This may support dashboards that API-based submitters could utilize.

- User Onboarding

- Allow individuals or organizations to delegate representatives for account setup and management. This could reuse CMS I&A

- Organizational users can fill out a form to build out their directory resources in NPD

- Self-Service Pages

- Let users view and update their own or their organization’s data

- Restrict edits to only the data they submitted in the portal; users should not be able to edit data submitted via API

- Optional File Uploads

- Enable bulk data entry through a file submission for organizations updating their data

- An EHR could offer a bulk directory export feature, and a user at a small organization could use this feature to easily update their organization’s directory entry in NPD

- Organization Structure Review

- Provide a summary view for organizations to verify their hierarchy before submission

- Create a page for an organization to see a review summary of their reported organization structure and hierarchy so they can verify it before (or after) submission

2. Organizational Identity

Since a healthcare organization might submit data to the NPD through various channels (like different networks or EHR systems), a clear system for managing identity is crucial to prevent duplicate records and ensure data integrity.

Establish the Legal Entity Concept: Define and support a unique identifier for the top-level “legal entity,” representing the full organization responsible for submitted data. This concept is broader than a billing entity (Type-2 NPI) and is necessary to aggregate data submitted from multiple sources under a single organizational owner.

- This could be represented by a top-level ManagingOrganization resource in the NPD

- The TEFCA directory employs a similar concept (the “TEFCA ID”) to associate entries from the same legal entity submitted by different sources

Attribute Ownership to the Legal Entity: Tie resource ownership in the NPD to the legal entity, not just the API client, allowing an organization to manage its data cohesively across different submission methods.

(Optional) Expand the Web Portal to Support “Legal Entity” Management: If the web portal is built on I&A it will only support individual providers and billing entities, which are often subunits of legal entities. It should be extended to support multiple billing entities’ directories being managed together by an administrative user representing the legal entity.

3. Federated Connectivity

Shift from individual point-to-point connections to a federated model using CMS Aligned Networks for more scalable onboarding data exchange.

Deduplication Policy: To prevent data conflicts, organizations must either:

- Submit each data element through exactly one network or attribution source

- Take full responsibility for deduplicating their own data if they choose to submit the same data from multiple networks

Organizations should be able to choose the network that shares their directory entries to prevent duplicate data. Build a workflow for an organization to choose what network submits its data.

Data Submitter Requirements: Define and enforce standards for network participants, including timely data updates, minimum data quality thresholds, and timely response to data quality flags.

Standardization:

- Define consistent submission formats and interpretations of FHIR resources, particularly the Organization resource hierarchy; allow for flexibility, accommodating submitters with varying levels of detail in their organizational structure; it should be valid to associate all providers with the top-level legal entity if granular facility structure data is unavailable

- Clarify expectations for sharing internal versus public API endpoints

(Optional) Point-to-Point Connections: For organizations that do not align cleanly with a single network or system—and are too large to use the NPD portal—a one-off integration with NPD may be required. To support such organizations, define an application workflow that allows them to assert their organizational identity and gain submitter access to a secure API for data submission.

4. Core Service Enhancements

Provenance Tracking: Automatically generate Provenance resources for all create, update, and delete transactions to capture the submitter identity and a timestamp for each change. This information should be surfaced in the NPD web portal.

Data Validation: Implement server-side validation rules that go beyond basic FHIR profiles, such as comparing submitted Practitioner data against existing demographic information to detect inconsistencies. Introduce API rate limiting to prevent system abuse.

5. Data Quality Reporting and Resolution

Establish a mechanism for users to flag incorrect data.

Implement an API for managing these flags, using FHIR VerificationResult or Task resources to track them. The specification for this API should be detailed in developer documentation and iterated upon through testing.

Post weekly/monthly data quality flags in a flat file repository.

6. Federal Provider Data Alignment

Option 1 – Migration: Migrate existing NPPES provider and organization onboarding and data management workflows into the NPD portal to create a single, streamlined process.

Option 2 – Synchronization: Maintain NPPES as the authoritative source for core Practitioner identity data. Providers can update their Practitioner entry in NPPES.

7. In-Network APIs

Encourage payers to share their Da Vinci PDex Plan Net directory endpoints in NPD.

Avoid deduplicating payer data about provider organizations into NPD directly.

(Optional) CMS could build a service to consolidate network data from various payer Provider Directory APIs.

8. Developer Tools and Documentation

Create a developer sandbox.

Publish a formal implementation guide for NPD, potentially through a standards development organization like HL7.

9. (Optional) Location Normalization

Location Normalization: To reduce duplication of Location resources, use a service like the USPS Address APIs to normalize and standardize address-level Location resources.

- Parent locations (e.g., address, city, county, state) can be auto-generated from USPS data when needed; this would create a set of shared, trusted Location resources not owned by any single organization

- Organizations submit and own child locations like floors and suites

10. (Edge Cases) Onboarding and Offboarding, Mergers and Acquisitions

Lifecycle Management: Define clear processes for operational edge cases, such as transitioning an organization from manual management in the portal to API-based submission, bulk reassignment of organization identifiers during mergers and acquisitions, and delegating control of directory entries.

Figure 9: The federated NPD directory after Phase 1; provider and payer directories are not integrated, and payers’ networks and APIs to share network status

C. Future Workstreams

Once the technical foundation of NPD is completely built, further work will still be needed to elevate NPD to a trusted source of truth for provider and payer data. This requires achieving superior data quality, establishing stable identifiers for key entities, and integrating provider and payer data. The goal of this phase is to slowly “raise the bar” on data richness and data quality and unify the provider and payer data in the directory. After piloting this with a small group of health systems and payers, adoption mandates can start to be introduced.

- Goals for CMS:

- Focus on improving data quality, adoption rate, and data stability of NPD. Encourage payers to associate networks with provider organizations’ PractitionerRoles

- Establish NPD as the single workflow and source of truth for basic provider-location-networks data

1. Improving Data Quality

Develop and display data quality metrics (e.g., duplication rates, completeness, timeliness of corrections) in a “report card” on the NPD web portal for organizations to monitor their performance.

Automated Data Correction: Implement workflows for automated data management. For example, a Practitioner record flagged as inactive (e.g., provider is retired or deceased) could be automatically deactivated after a set period.

Self-Service Data Correction Workflows: Allow individual providers to use the NPD web portal to disassociate their identity from PractitionerRole, Organization, or Network resources that have been improperly attributed to them.

Send alerts to providers when an organization submits data about them or removes the provider from their directory. Providers should have a self-service workflow to remove incorrect connections to organizations they are not affiliated with, and send a data flag to their system for a correction.

2. Governance

Create a “rules of the road” for data submitters to build trust and cooperation, prevent abuse of features like data quality flagging, and set a baseline for obligations and expectations.

Define an adjudication process or pathway for disputes about data ownership or quality.

(Optional) Attestation and Verification: Implement the attestation and verification specifications in FAST NDH to handle cases where two sources might attest to the same data, or data needs to be regularly verified.

- Evaluate if or how often regular verification requirements are needed

3. Advanced Enumeration and Stable Identifiers

Align payer and provider data in NPD by connecting provider organization and payer network resources. To do this, standardized, reliable enumerations for provider-service relationships that both providers and payers can trust are necessary, so payers can use provider data from NPD.

- Standardize Organization and PractitionerRole Resources

- Define a standard for Organization hierarchy (e.g., Brand > Regional Brand > Location > Department) that reflects the care delivery structure (as opposed to the billing structure)

- Require that the PractitionerRole resource be associated with the most granular Organization level available

- Enforce the immutability of a PractitionerRole’s core attributes (Organization, Location, Practitioner). If any of these change, a new PractitionerRole must be created and the previous one deactivated; this ensures the stability of the PractitionerRole identifier, which is critical for downstream use cases like referrals, claims processing, and payer enrollment

Enforce Sharing Organization Hierarchy: Require sharing complete Organization hierarchy and sharing providers at the most granular level of this hierarchy (department-level).

Promote Identifier Adoption: With complete and reliable data, the Organization and PractitionerRole identifiers are ready to function as new NPI-like enumerations for service and provider locations, adding significant value to both payer and provider workflows.

4. Service Finder

Implement the FHIR HealthcareService resource to enable service discovery. CMS should restrict HealthcareService resources to a small, CMS-managed standard set of patient-understandable services to ensure cross-system interoperability of services. These resources will function as standardized “tags” linked to PractitionerRole or Organization resources to represent high-level specialties, common conditions, or other patient-facing services. This can power provider lookup functionality for patients, or help providers find a recipient for simple referrals. Attestation of these services should be optional.

5. Networks

Enable and encourage payer organizations to share Network resources with their insurance plans by associating them with provider organizations’ PractitionerRole records.

- This model requires payer submitters to have write access to PractitionerRole resources that they do not own, as the reference to a payer’s Network is stored within the provider’s PractitionerRole; the system must enforce strict access control mechanisms to ensure that payers can only modify references to their own Network resources within a provider PractitionerRole, or implement a FHIR extension to change the data model

- Payers are encouraged to expose APIs capable of determining whether a given PractitionerRole and CPT/HCPCS code pair is covered in a given network or plan

6. Credentials

Allow for state licensing boards and other professional credentialing bodies to be direct data submitters into NPD, associating data into the Practitioner resource.

7. Single Source of Truth

With both a technical foundation and a reliable foundation, CMS can now focus on establishing NPD as the single source of truth that patients, payers, and providers rely on for basic provider information and in-network checks. There should be sufficient time before this step so that providers, provider organizations, payer organizations, and technology vendors have time to shift to NPD. This could start with a small group of pilot organizations, providers, and payers.

- NPPES Requirements: Create a plan to sunset NPPES and shift provider and organizational requirements for onboarding and regular data updates from NPPES to NPD

- Offer incentives or grants to smaller clinics and FQHCs to help with initial onboarding to NPD, or delayed onboarding requirements for smaller organizations

- Quality Designation: Create a program to vet and designate submitters who demonstrate high data quality; participation and good data quality in NPD could be tied to incentives like MIPS; scores could be based on having good data quality metrics, or documented processes for data review, corrections, and ongoing maintenance

- No Surprises Act Enforcement: Shift No Surprises Act enforcement expectations to allow providers and payers to use NPD to achieve compliance

- Providers fulfill the No Surprise Act obligation to regularly submit basic provider directory updates to payers by submitting to NPD

- Payers may still require portals for plan enrollment

- Payers fulfill the Good Faith Estimate APIs requirement by sharing an API in NPD that consumes an NPD PractitionerRole and a CPT/HCPCS code

- Payers use NPD data to fulfill the No Surprises Act obligation to keep their provider rosters up-to-date with basic provider data updates from provider organizations

- Patients can rely on NPD as audited proof of in-network status

- Providers fulfill the No Surprise Act obligation to regularly submit basic provider directory updates to payers by submitting to NPD

- Provider Directory API: Shift the Provider Directory API requirements away from payers offering an individual, payer-specific provider directory API to participation in NPD

Figure 10: Provider and payer data can now integrate, with payers able to connect their networks to provider PractitionerRole resources

Epic is a proud sponsor of Healthcare Scene.